I have become friends, over the internet, with Keith Jones, who is vice-president at URS Corporation in Little Rock. His company specializes...well let me paste from their website..."URS Corporation is a leading provider of engineering, construction and technical services for public agencies and private sector companies around the world. The Company offers a full range of program management; planning, design and engineering; systems engineering and technical assistance; construction and construction management; operations and maintenance; and decommissioning and closure services for federal, oil and gas, infrastructure, power, and industrial projects and programs"

They are presenting a proposal to the Northwest Arkansas Regional Planning Commission regarding the development and feasibility in the future of light rail travel in Northwest Arkansas.

Keith emailed me a couple of years ago about Bentonville railroads and history and especially of the Interurban railroad. It made me think that now would be a good time to explain the old rail line and it's story.

Monte Harris provided this picture which is a favorite photo among those looking for information on this old line, courtesy of the Rogers Historical Museum:

The train itself reads "Bentonville Park Springs and Rogers." According to the section on the Interurban in J. Dickson Black's History of Benton County, talk of the first trolley in Benton County began in 1912 when a charter was granted to the Arkansas Northwest Railroad Co. to run an interurban train between Bentonville and Rogers. The company got the franchise from Rogers to operate its car down the center of second street from Cherry north to the intersection with the Frisco track which ran to Bentonville.

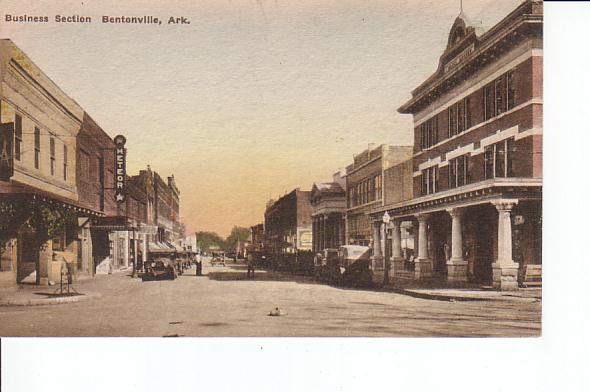

In Bentonville they left the main Frisco line just west of the Bentonville Station.

The rail would have turned north just in the foreground of this picture.

The rails ran right down the middle of the street. The train stopped at the Massey Hotel, then continued on to Park Springs Hotel at the north end of town.

On July 1st, 1914, several hundred Bentonville citizens and a band went to Rogers on the first trips of the new motor car, and an informal reception was held. A little later Rogers returned the call and a dinner and picnic was held at Park Springs.

The fare was 15 cents at first and the car made several trips each day. The motor car, as Black called it, was not always reliable and missed a good many trips. But this was alot better than have just one run a day like the Frisco made with their train that ran from Rogers to Grove, Oklahoma.

The train was far different from any the people in Benton County had ever seen before. It was a big red coach trimmed in black with gold lettering. The engine was in one end of the long coach and next to this was a small baggage room. The coach was 92 feet long inside. The passenger part seated about 130. Sometimes there was standing room only.

The line was owned by J. D. Southerland, that is, he owned both ends of it. Mr. Southerland came to Bentonville in the fall of 1913, and bought the Park Springs Hotel. At that time it was a large and beautiful summer resort. But it was hard for people to get from the Frisco station in Rogers to the hotel.

Mr. Southerland made a deal with the Frisco Railroad line to run his train on their track from Rogers to Bentonville. The only trains running was a passenger train to Grove that went out in the morning and back at night. Then there were a few freight runs. Mr. Southerland made his runs between these.

The Rogers station was just a roofed over platform a block from their Frisco station. There was a shop and shed at the Bentonville end of the line, and the train was kept here overnight. At that time the streets were all dirt, so when they laid the track they used short ties and built the track in the center of the road. The wagons and what few cars there were had to drive on both sides of the track.

"The Interurban filled a need at the time when it was built," said Henry Cavness, one of the last men to die who had worked on this train. "I was the brakeman the whole time the train ran. There were several motormen, among them Ed Largette, Ben Guol, Art Mayhall, and Jake Kohley. Bob Fowler and a man named Ketter were the comductors. We used just a three man crew to run the train. We hauled mail between the two towns and always met the trains that ran on the Frisco main line. The tourist going out to stay a month at Park Springs sure would have a lot of baggage. Sometimes we would fill the little baggage compartment."

The first run left Bentonville at 615 in the morning and the last run got back to Bentonville at 1130 in the evening. They stopped at Cherry and Walnut Streets in Rogers, then at Apple Spur, Arlan Spur, Massey Hotel and Park Springs Hotel.

In the evening there was always a good crowd riding. They could go to the picture show or visit in town. In the summer whenever there was a ball game, fair, or carnival in either of the towns, the coach would be full every trip.

The rate was raised to 40 cents for a round trip, one way 21 cents; 5 cents from the Massey to Park Springs. They had a ticket office in the Massey Hotel; this was also the business office. Most people just paid when they got on. This train stopped almost anywhere along the line to pick up or let off passengers.

"The only time we ever had any trouble was when we had a full load," said motorman Jake Kohley. "I remember one night in the summer of 1915, it was the last run and there had been a carnival in Rogers, and we had a load of about 150 people. Someone had opened the switch at the edge of Bentonville; when we hit that it knocked the wheels off the car. We were very lucky no one was hurt. But a lot of them had to walk home...The auto took the place of the trolley but it seemed to me a lot of fun of the trip went out when the trolley did."

The motor car made its last trip June 11, 1916, when the Frisco railroad ordered it off their tracks for non-payment of lease dues.

At about this time Mr. Southerland lost or had to sell most of his holdings here. Soon the track was taken up, the coach sold and the line was no more. But old-timers still talk about the trips to Bentonville or Rogers, or a trip to Park Springs for a picnic that was made on the Interurban. (that was in the 1970's that Black did his research.)

The only one who ever talked of the bad parts of the line was a man who drove a team to a freight wagon. He said,"The ties stuck out so far that if you were not careful a wheel would hit one and could throw you right off the wagon. But it had its place, just as the horse once did, but they are both gone now."

I have done a lot of searching but I have yet to have found any old tickets, baggage claims, photos of the storage shed, or especially any sign of where the unique train went once it left Bentonville and was sold.

Robert Winn, railroad expert, has the most accurate description of the engine in his book Railroads of Northwest Arkansas. He called it a "knife-nosed McKeen car with distinctive round porthole type windows. " I have searched all of the records at my disposal but have come up short on whatever happened to it.

The internet has some beautiful pictures of this same type of engine, especially the one restored for the Nevada State Railroad museum in Reno.

Don't you know that this beauty would have caused a stir travelling down Bentonville streets?

Here is the interior view:

You can follow this link on Youtube to see Reno's old engine in action after restoration:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YmOSWNmjfsY

The north end of Bentonville was a popular recreation spot during those years. The big Park Springs Hotel had a pool, cabins, and several springs that were thought to have had healing powers. There was a large baseball park somewhere around the area of what is now NW A and 10th probably lying to the east. It was known as the Blackjack ball park. The area around Park Springs was not even annexed into the city limits until the 1930's.

Maybe someday soon the trains will run again, carrying passengers from Fayetteville to Bentonville and back, in hopes of alleviating some of our traffic woes. We shall soon see.